Margo W.R. Steiner writes: “I have a question for which I have never been able to get a satisfactory answer, including from The Chicago Manual of Style! My question is basically this: If a word was once an acceptable word, doesn't it continue to be a word, at least in unabridged dictionaries? Although it may now be considered archaic, doesn't it still deserve a place in any respectable dictionary, with the caveat that it is archaic?

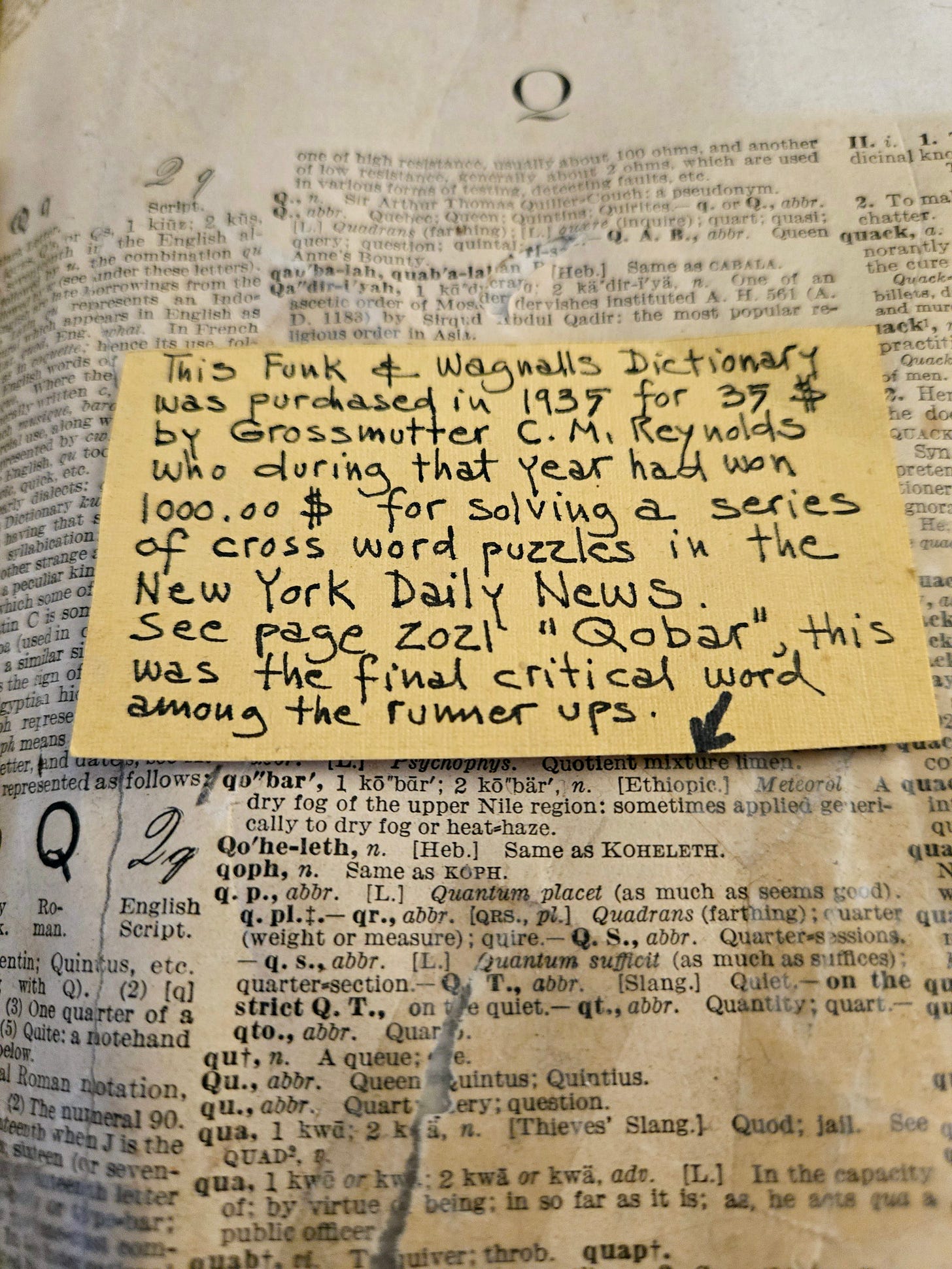

“My question specifically deals with the word qobar, one of the few q words without a following u. As you will see from the note my ex-husband placed in [his grandmother’s] now nearly 90-year-old dictionary, she was a winner in a New York City-wide crossword contest in which one of the answers was qobar.

“I love the word but have discovered that is no longer in any dictionary. Personally, I try to keep it alive by dropping it into conversation whenever I can!

“Once it’s a word, how can it be entirely erased from our language?”

Margo, language reference sources come in many varieties, and a stylebook such as the Chicago Manual isn’t the likeliest place to find an answer to your question. But I checked my no-longer-young Webster’s New Twentieth Century Unabridged Dictionary of the English Language, Second Edition, for you and didn’t find qobar there. My Webster’s Second, though, is the 1970 revision of a book that was first published in 1934 — so all this tells us is that qobar wasn’t current 55 years ago.

The dictionary’s introduction explains about its most recent revision:

The entire list of entries in the dictionary was re-examined on the basis of modern word-count lists. Words whose increased use in recent years had established them as a part of the active vocabulary of American English were inserted, and such rare or esoteric words as had virtually disappeared from active use were dropped from the word stock to make room for the newer, more pertinent entries. The constant criterion for entry selection was the probability of usefulness to the reader.

That is, not even a dictionary that runs to 2,129 pages has space for everything. The print Oxford English Dictionary published in 1971 has nearly twice that many pages, and it doesn’t give qobar either.

All the same, you might well wonder why current online dictionaries that claim to be comprehensive or unabridged do not include everything their earlier editions ever included. All dictionaries had space constraints before they began to be published online, and I assume the words that were in the last print edition are the only ones that got transferred over; reinstating archaic words that had been cut for lack of use would be an expensive and quixotic undertaking. The archaic words that are still given tend to be ones that appear in literature that remains well known.

I hope you’ll be heartened to know that qobar does appear online in Wiktionary and Power Thesaurus (thesaurus or not, it doesn’t offer any synonyms for the word). These resources would have more readily incorporated the word than legacy dictionaries could, because they were created relatively recently, are compiled by their users, and have very different business models. So qobar hasn’t been “entirely erased” — just sidelined.

Email me with your language questions, peeves, problems, etc., at barbaraswordshop@gmail.com, and I’ll respond as soon as I can. Correspondence may be edited. If you subscribe to The Boston Globe, look for my column, “May I Have a Word,” in the Ideas section every other Sunday.

Qobar is going to be my new word. However as usual I will be slightly editing the definition or usage of said word. For example, when going out for a night of drinking I will be qobarring. Also politically to qobar is to speak as if in a hazy fog as in: “I couldn’t understand a thing Trump said as it was just a qobar”. Additionally Trump himself might use it as in : “I am qo(ing to)bar everyone I don’t like from receiving any social security checks”. Another derivative might be qobarf, which can apply to any of my prior definitions.